Before the war, David Cervinschi, son of Aron-Josef Cervinschi, lived in Kishinev, with his wife, Clara, and their two sons, Samuel and Shraga. In 1941, they were confined to the city's ghetto. Only 37 ghetto detainees managed to escape; the Cervinschis were among them.

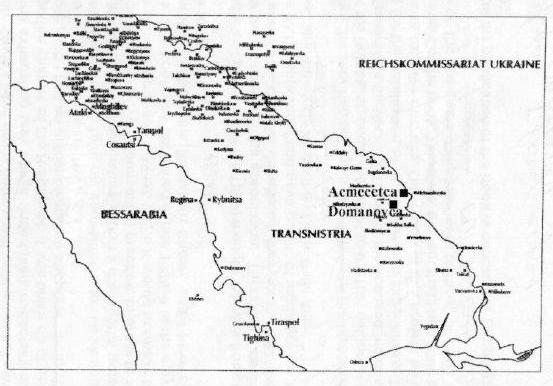

The two adults were later recaptured and deported to Transnistria, where they were interned in the camp of Domanovca; the two boys remained in hiding, in Romania. David and Clara survived, and, at the end of the war, they returned from Transnistria. In the spring of 1944, the four members of the family were reunited in Bucharest; however, many members of their extended family perished.

Just a few months after their reunion, the Cervinschis immigrated to Palestine.

| I have tasted the bitterness of things, but I have found nothing that is so bitter as the taste of begging. |

| Solomon Ibn Gabirol (1021-1058) |

|

The historic background to this testimony was provided by Professor Samuel Aroni<1>, David Cervinschi's son.

The province of Bessarabia was inhabited by Jews since the 16th century. They were involved in all facets of life from tradesmen to merchants, to intellectuals. The Jewish community had developed a wide spectrum of vital, energetic institutions in the fields of education, printing, theatre, etc. In 1918, there were 207 active synagogues and about 14,000 students were enrolled in the 443 Jewish schools across Bessarabia.

Kishinev was the main city in Bessarabia. The census of 1897 lists the Jewish population of the city at 50,237. In June 1940, when Bessarabia, then under Romanian administration, was ceded back to the Soviets, the Jewish population of Kishinev grew to about 60,000- 65,000. This was mostly due to an influx of Jews fleeing the Fascist regime in Romania. On June 22, 1941, at the onset of the Romanian and German attack on the Soviet Union, many residents of Kishinev were killed during air raids; among them, the renowned Chief Rabbi Zirlsohn. Before retreating eastward, the Soviets set the city ablaze. The flames raged for three days and nights prompting many residents to flee the mayhem. On the Sculeni road, to the north and on the Hancesti road, to the south of the city, Romanian and German troops killed about 10,000 Jews who were trying to flee.

On July 17, 1941, German and Romanian army units entered Kishinev, followed shortly by the infamous German Einzatsgruppe D<2>. A number of small-scale massacres of Jews ensued. A few days later, the remaining Jews were herded into a ghetto, which had been hastily established in the old part of the city. Of those who had managed to escape from the ghetto, most were later recaptured, including the Cervinschis. According to Romanian records, the Kishinev Ghetto had a population of 11,525 Jews. The ghetto was surrounded by a tall wall with several guarded gates. From the beginning of August to the end of October 1941, periodic selections and subsequent killings took place in the Kishinev Ghetto. At this latter date, the ghetto was emptied and the remaining residents were force-marched to Transnistria. By December 1941, only 86 Jews were left in Kishinev.

It is estimated that during World War II ninety percent of the Jewish population of Kishinev (about 53,000 people) perished through pogroms and deportations.

(The following testimony was translated and edited from The Destruction of the Jews of Bessarabia. The Hebrew version was published by the Committee for Bessarabian Jews, Tel-Aviv, Nov. 1944, p. 27-30.)

The name of the Acmecetca death camp came from a nearby large Ukrainian village, in the Domanovca area, the district of Golta, which was along the western bank of the River Bug. In a valley, about two kilometers away from the village stood four large pigsties built of clay and covered with straw. Before the war, thousands of pigs were bred and raised there. A few wooden barracks and a couple of stone houses had been built on the nearby hill for the use of the pig farm workers.

During the hard winter of 1941-42, many Romanian deportees became too ill and too weak to continue the hard labour in the fields or at road and bridge building. Consequently, the Domanovca area officer, attorney Balunaru, proposed a selection of the feeble ones who would be sent off and interned at the former pig farm in Acmecetca. The rationale for this decision was "so that they would not consume any more food and would die of hunger and thirst".

Following his subordinate's proposal, the Jew- hating governor of the Golta district, Modest Isopescu, ordered a selection to take place on May 10, 1942. Weakened and sick deportees, including many elderly, women, and children, were amassed from all over the Golta district and taken to the pig farm. That terrible place, to be labeled "der toiten lager" (the death camp), was surrounded by barbed wire and a deep trench. Ukrainian police was used as guards. Those who tried to escape were shot on the spot. At various times, thousands of people were imprisoned at the Acmecetca camp. The detainees were forced to live in the most inhumane conditions, without food or drinking water. Those who had managed to hide some money or jewelry, would give it to the guards, in exchange for food: a piece of bread, a piece of fruit, or anything edible.

Those of us who were sent to work outside the camp had learned from Romanian soldiers of the horrors our loved ones were subjected to. The news from Acmecetca was shocking; we heard about people dying by the hundreds from starvation, yet, we were powerless to do anything about it. Deportees were not allowed to move from one camp to another; those who did were apprehended and shot on the spot. Nevertheless, we felt that we had to do something for those at Acmecetca.

Eventually, we managed to organize a semblance of a Jewish committee in Domanovca, of which I was a member. The committee has sent numerous petitions to the Romanian authorities, asking for permission to help those in Acmecetca, but to no avail. Finally, in July 1942, through bribery and further pleading, we finally got permission to deliver a weekly cart of food to the people at the pig farm. We, the "healthy" ones, were starving too, yet we decided to observe a day of fasting each week, in order to save part of our meager food ration for those doomed to die in Acmecetca. Soon, we were able to supply them with a cart of food every week.

One Sunday, at the beginning of August 1942, I was a part of the group chosen to deliver the food. As we approached the camp, the most terrible sight was revealed to me. Many of the detainees stood by the fence, waving and shouting frantically. As I came closer, I saw a crowd of bare-footed, half-naked bodies, some wearing only loincloths. There were men, women, and children, dried out and skinny, like bare sticks. Dirty, their hair long and unkempt, some were crawling on their hunger- swollen bellies and eating thin blades of grass off the ground. Several decrepit women were attempting to boil something on a smouldering fire. When those unfortunate people saw us bringing the food, there was such a wild outburst that we feared for our lives. We had to push the cart some distance away, and chose one of us to guard it. The cart contained 96 loafs of bread, 10 bottles of oil and 5 kilograms of salt. I cut each loaf into five pieces, thus, I was able to give a piece of bread to each of the 600 people -- the survivors from the thousands who had originally been interned there. Before we, started distributing the food -- which was meant to last until our return the next Sunday -- I asked the inmates to enter their pigpens.

Inside the pens, I saw people who were too weak to stand up; yet, the will to survive was burning in their eyes like a fire. Among them, I recognized people with whom I had made the terrible death-march from Kishinev to Transnistria. I had known them as strong and healthy people; now, they could hardly lift their hands to grab the piece of bread they were handed. In some of those pens, I saw the remnants of notable families, like the mother and two sons of the Hertzberg family, from Soroka. The head of the family, one of the wealthiest men in that town, had died. The sight of the young ones was the most heartrending. They begged, they did not want to die; yet, they hardly had the strength to live. On my way back to Domanovca, I managed to fill the cart with tomatoes I bought from the nearby farm of Duca Voda. Thus, I returned to Acmecetca and distributed that too. The detainees were overjoyed. "Cervinschi, have pity on us, give us a few more tomatoes; we want to live,. don't let us starve!" I also gave them whatever money I had left in my pockets.

As I was preparing to leave that horrifying place, I found myself in a very disturbed state of mind. That is when the manager in charge of the nearby farm, who also supervised the Acmecetca camp, stopped me and requested that I gather the detainees for an important announcement. The people gathered slowly, as if they knew that no good news could come from the authorities. The manager asked me to translate his words, as some of the inmates spoke only Ukrainian and Yiddish. He suggested that, since the rain and snow season was nearing, the deportees could start making bricks, building stoves, and repairing the roofs, while the "healthier" among them should start gathering scraps of wood. To that "generous" and "humane" offer, the deportees replied unanimously: "We don't want stoves! We would rather die than live through the winter in these conditions! If he authorities plan to keep us here, they better bring machine-guns, kill all of us now, and get it over with!" The desperation in their eyes was to remain etched in my mind for a long, long time. As I walked away, they kept on crying: "Don't forget us, save our souls!" I finally left, with a broken heart. To this day, I often hear the whimpering voices and see the shadows of the living dead in the Acmecetca death camp.

The Last Message

Aron-Josef Cervinschi, David's father, was a Hasid of the Skvere Rebe, an independent businessman, and a well-known lay cantor. In October 1941, during a wave of deportations, he was herded with his wife on a death march from the Kishinev Ghetto to Transnistria. He was 69 years old at the time.

Since the deportation, the remaining family heard nothing about their fate, except for the postcard reproduced below. It was written on the way to Transnistria.

That post card was the last sign of life from Aron-Josef Cervinschi, David's father. It was written from the village of Orhei, somewhere on the trek to Transnistria.

The text in the postcard is coded. The decoding was provided by Professor Samuel Aroni, Aron-Josef 's grandson.

David Cervinschi and Ghenea Fisman, brother and sister, were the children of Aron-Josef Cervinschi. David lived in Kishinev, while Ghenea had married a man from Iasi. Thousands of Jews from Iasi were murdered in the summer of 1941, during a ferocious pogrom. "David's move 12 days ago" is a reference to his escape from the Kishinev Ghetto. In the postcard, Aron- Josef is urging his daughter and her family to move, at all costs, to Palestine (where his brother, Nuta, lived), considering the impending danger of further pogroms and deportations. At the end, Aron-Josef expresses his hope that they would all meet again in Palestine, at Nuta's.

That hope would, unfortunately, never materialize.

Footnotes

[ Previous |

Index |

Next ]

Home ·

Site Map ·

What's New? ·

Search

Nizkor

© The Nizkor Project, 1991-2012

This site is intended for educational purposes to teach about the Holocaust and

to combat hatred.

Any statements or excerpts found on this site are for educational purposes only.

As part of these educational purposes, Nizkor may

include on this website materials, such as excerpts from the writings of racists and antisemites. Far from approving these writings, Nizkor condemns them and

provides them so that its readers can learn the nature and extent of hate and antisemitic discourse. Nizkor urges the readers of these pages to condemn racist

and hate speech in all of its forms and manifestations.